home

current issue

featured poet

poem of the week

lives of the poets

poetry near you

reviews

archives

subscribe

donate

about us

contact us

What Is There: James Schuyler

reviewed by Richard Wirick

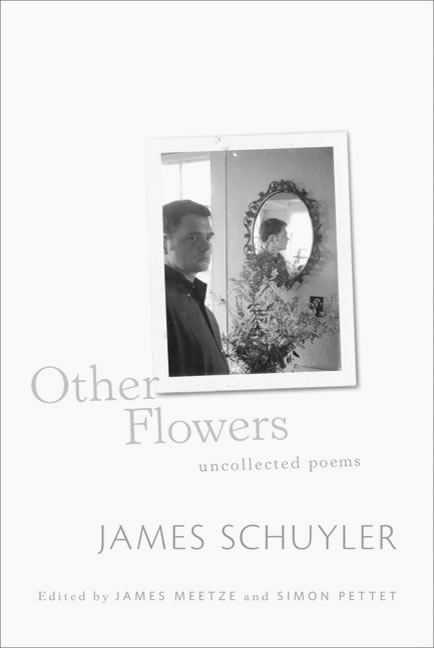

Other Flowers: Uncollected Poems

Other Flowers: Uncollected Poems

James Schuyler

Farrar Straus Giroux

James Schuyler was the best of what has come to be called the “New York School” of poets, the most accessible and passionate and direct. John Ashbery was the cerebral conjuror, a radio tower drawing in pop and rococo frequencies from every location, every periphery. Kenneth Koch was straightforward enough, but never entirely fused the pictorial with an inner “felt life.” Frank O’Hara was playful, cool, conversational, and unquestionably pictorial — the “poet among painters” as Brad Gooch put it — as he charmed and seduced and walked away with the lonely listener’s heart. But Schuyler, “Jimmie” to his friends, was the most American of the New York Poets, the most plain-spoken and universal, the constant hunter and gatherer of the vernacular.

Schuyler always told us exactly what he saw, and dressed it in so thin an art that its presence, though never its effect, was nearly invisible. His lines were “like gold to airy thinness beat,” in the words of his beloved Donne. As with Ashbery, the range of his vision was never static — he included, to the extent it built up the little comic frames of his stanzas, “whatever is moving.” (The phrase is from an essay on Schuyler by Howard Moss, The New Yorker’s long-time poetry editor, in a book he so titled.) My mother-in-law, a friend of Moss’s, claims he never stopped talking about Jimmie, greeting each new poem with hands in the air, fingers extended, like a blind man given a sudden stroke of vision.

The easiness of his lines and cadences were never trite or contrived. Though he arrived with an offbeat, startled surprise at the described object or situation, his expression was as gripping, elegant, and emotionally layered as any effect created by formalists. As idiomatic and offhand a poem as “A Heavy Boredom” plunges us through the ravaging emotional registers the seasons bestow, suddenly and without pity:

I had sooner go bare

than sit pent in a business suit

O how this chafing burns me!

not even Johnson’s baby powder

soothes: my soles are creased and my

pits are cranky and damp and sticky.

For is Summer come

the lucky ones are sportive,

from Maine to Key west

I like Southampton best

or perhaps a tourmaline lake

like a tear in the heart of Vermont.

Too many skeletons. Scribble,

the trees grow thin,

won’t winter come, Coppelina?

Another lovely weather poem is a simple quatrain: “The wheeling seasons turn / summers burn / then all fall fallow / in ripe yellow.”

Schuyler’s immense emotional resonance roils like smoke across the “collected uncollected” poems of Other Flowers, just out from FSG. One commentator calls him the supreme poet of articulated consciousness (Dan Chiasson), and remarked that Schuyler’s “blood brother” Ashbery once said that Jimmie “made sense, dammit”: not a virtue in itself (plenty of simple-minded poets make sense), but when joined to a mind this multifoliate, subtle, and searching, proves something akin to a miracle. Chiasson saw him as “the poet of ingrown courtesy, gossip in a vacuum, remembered friendship, and the one-on-one encounter.”

And it’s true. Schuyler reaches out for companionable hearts in order to understand — and portray — the uncertainties and dreads of any heart. Like O’Hara, who claimed anything he wanted to do in poetry could be accomplished by picking up the telephone, Schuyler needed to extend his mentalism to someone as flailing and stunned as himself for it to come into focus. And what focus he gives it! The poem “Help Me” (from Vincent Price’s The Fly?) starts out:

Help me

find the paradox I look for:

the profoundest order is

in what’s most casual, these humped and cat-

ty cornered cubes, the wind,

so you’re planning to be sad

or casual

as a hat

off a yacht,

afloat

in a cove.

If poetry is “emotion reflected in tranquility” (Wordsworth), Schuyler can only reflect with a companionable ventriloquist’s dummy on his knee. He is pulling the string of his mind’s odd twin, a yammering, downtrodden Chatty Cathy. He was frightening when in his manic swings (see “The Payne Whitney Poems” in the Collected), and when ebullient, was inseparable from his valiant but impatient patrons. Incapable of solitude, his verse and his very viscera were an extended, lifelong, late-night set of eerie duets.

Sometimes Schuyler’s speaker and his Other switch places, dream-morph into one another, fuse and separate and trick the reciprocal companion, all of it working up a slapstick of droll chatter and passing perceptual traffic:

4N

The hospital’s elevator is very slow;

it stops at every floor. Finally,

four. You knock on the battered

metal door of Ward 4N. A nurse

unlocks it and you ask to see

your friend. “I don’t know if

he can have visitors today. Sit

here.” She vanishes. The shabby

room is all too familiar (I’vebeen there myself). Time passes.

“Got a light?” a patient asks.

The light is given. Someone is

Running. It’s my friend, saying

my name. I call to him: he doesn’t

hear. He’s trotting, all bent

over. Then he goes back: to his

bed, I suppose. “You see?” the

nurse says “He can’t have

visitors today.” “Is there any

point in my coming back to-

morrow. “You might. He might

snap out of it.” She unlocks

the metal door. That damned

elevator takes forever. In

the street it’s hot and humid

and I sweat, and people walk

freely; going about their business.

Articulated consciousness and emotional interiority are here pressed outward onto minimalist characters — like Beckett stage figures — and given enough action to form a stoic comedy.

Feats like this take us ultimately to Schuler’s treatment of inanimate “things-in-themselves,” his still lifes, the “natural object” as the only permissible symbol Pound would permit the poet. And here once again, his touch was so delicate and true as to be nearly photographic, hyper-real, letting the seen thing sustain its own textures and hues and substance, irrespective of the knowing subject. The poet’s transformation is so subtly detached that the object almost seems to throw it off, making its own claim on time and significance. Like the Christ in the frescoes of Raphael, things seem to say Nolo me tangere: I do not require a perceptual field for my sustenance. The poet concedes in “Dandelions”:

Hooray

for a change

I’m letting the sky

stay as it is

tomorrow the sun may come out

besides what’s wrong

with gray

you can almost put it

and shape it

smoke and dulled

lights hovering in it

like clay

The classic “Schuylerian detail” thus lets things stand almost on their own. Its scrupulousness was a tremendous experiment, a ravishing frontier for poetry to pass into. “No ideas but in things,” said William Carlos Williams. Schuyler seems to have it that the thing itself is the idea, though the addition of mental constructs adds an elevating, honest sheen, a newly necessary dimension.

To paraphrase Chiasson, if durable verse could be fashioned from mere flotsam and jetsam, things plain and unadorned, then poetry’s potential had become, in a very new way, almost infinite. This poesy of diffidence and near-indifference was groundbreaking. Its tricks of perspective and concern were successful, and beautiful, and will last until time breaks down all things but the beautiful.

Richard Wirick is the author of the novel One Hundred Siberian Postcards (Telegraph Books). He practices law in Los Angeles.

This review first appeared in Pacific Rim Review of Books #18