home

current issue

featured poet

poem of the week

lives of the poets

poetry near you

reviews

archives

subscribe

donate

about us

contact us

Korea’s Rainhat Poet

reviewed by Trevor Carolan

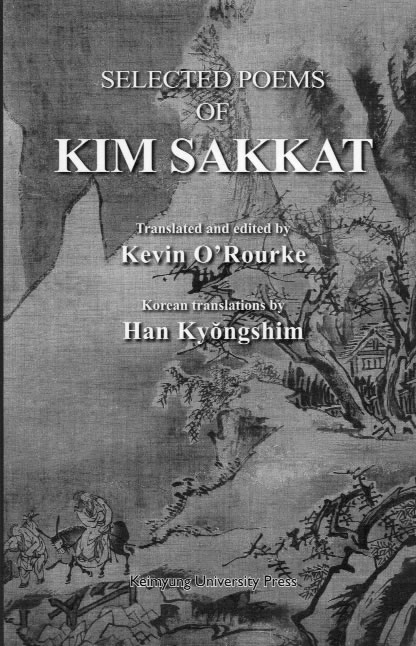

Selected Poems of Kim Sakkat

Selected Poems of Kim Sakkat

Trans. by Kevin O’Rourke

Keimyung Univ. Press.

Though one of his nation’s greatest lyric poets, Kim Sakkat ‘the Rainhat Poet’(1807-1863) is scarcely known outside Korea. Born Kim Pyong-yon, he remains an iconic, renegade figure in a country that has made the kind of sacrifices to achieve economic prosperity few contemporary North Americans or Europeans could understand. Koreans love an underdog; collectively they know the role too well, so Kim survives as a kind of beloved outlaw figure. When educated urban business people dream about chucking in their jobs and escaping the rat-race, the person they likely dream of emulating is Kim Sakkat— living free and easy as a wandering bard on the road. Until now, there have been few decent translations of his poetry in English. Now we have this first major gathering of his work for consideration.

In turbulent political times, Kim’s landowning family hit a downward spiral and he wound up as an itinerant minor yangban aristocrat, paying his way along the road like a Celtic bard or a delta bluesman, with spontaneous poems and songs for every landlord. As O’Rourke’s introduction explains, Kim was part of a new social and political phenomenon in early 19th century Korean society. Squeezed by China and Japan, and threatened by the expansion of Catholicism introduced in the south, a new class of landless scholars emerged—rootless intellectuals, Kim among them. His is the Cinderella story of Korean Literature: a suffering, broke, passionate genius—unexpectedly modern in style—screwed by an outmoded feudal system.

As the poems show, this is not the Tang-inflected Zennish work Westerners have come to love: Kim gives people what they want in poetry, but not in the ways they’ve come to expect. O’Rourke’s comprehensive introduction sets the collection up well with biographical information on Kim, his life and times with, notably for readers unfamiliar with Korean poetic tradition, a technical overview of its metrical and verse forms. It’s an uncommonly rich discussion of Korean poetry and poetics.

he Hanshi style Kim practiced involves the poetic use of Chinese characters. Among scholars, this too often resulted in stilted Korean poems that were poorly imitative of older Chinese models. Kim’s distinction, or notoriety, was to use this high-brow intellectual form to express the rugged vernacular of Korea’s early 19th-century common folk, and this makes him memorable. He’s as bawdy as the Elizabethans or Spaniards of the 16th and 17th centuries:

Second month; neither hot nor cold;

Wife and concubine are most to be pitied.

Three heads side by side on the mandarin duck pillow;

six arms parallel beneath the jade quilt.

Mouths open in laughter—thing p’um;

Bodies turn on their sides—stream ch’on.

Before I finish in the east, I’m at work in the west.

I face east again and deploy the loving jade stalk.

Drink and the natural world are never far off: “…I drink ten jars of red Seoul wine / In the autumn breeze I hide my rainhat / and head into the Diamond Mountains.” Tarts, drunkards, itinerant philosophers and sundry Buddhist adepts colour Kim’s poetic landscape.

In conversation once in Seoul where the translator has lived for more than 45 years, O’Rourke discussed links between Kim Sakkat and the classical Chinese and Japanese poetry of writers like Tu Fu, Wang Wei, Ryokan, and Basho—literary characters that have wielded incisive critical influence on the development of the Cascadia/Pacific Coast region’s eco-poetics. He further suggested comparisons to Celtic tradition with its bardic finger-pointing to beneath the surface of things; associations similarly, and favourably, arise with contemporary poets such as Mary Oliver.

In Korea, Kim’s poetry has been best loved among the kisaeng, the wine-shop singsong girls. With their job of seducing, none has suited their métier more than the Rainhat Poet:

At first we found it difficult to relate;

Now we are inseparable.

Wine Immortal and town recluse together;

Heroine and poet are one at heart.

We’re pretty well agreed on love;

A novel trio we make—moon, she and me.

We hold hands in moonlit East Fortress;

Tipsy, we drop to the ground like plum blossoms in spring.

The translations are readable and hold up to the originals well. O’Rourke captures Kim’s country Korean-isms better than anyone. Occasionally a leaner line might work, dropping conjunctions or use of the definite article, but this comes partly from our modern experience of reading poetry aloud more frequently. O’Rourke though, is a poet who translates poetry. He has given us the lion’s share of our fine translations from Korean poetry and this is a lively new addition. Welcome then, Kim Sakkat to the “renegade scholar” tradition—a fresh name to include alongside such Asian poetic character worthies as Nanao Sakaki and Ko Un.

Trevor Carolan’s latest work is The Literary Storefront: The Glory Years, 1978-1985 (Mother Tongue).

This review first appeared in Pacific Rim Review of Books #20