home

current issue

featured poet

poem of the week

lives of the poets

poetry near you

reviews

archives

subscribe

donate

about us

contact us

Those Godawful Streets of Man by Stephen Bett

reviewed by Richard Stevenson

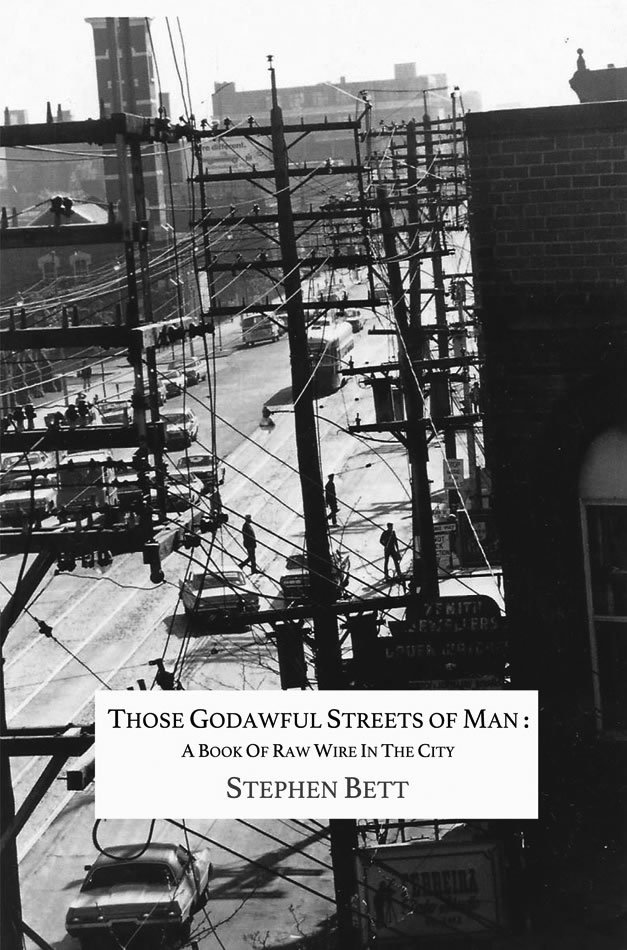

Those Godawful Streets of Man: A Book of Raw Wire in the City

Those Godawful Streets of Man: A Book of Raw Wire in the City

Stephen Bett

BlazeVOX (books)

2015

I love what Stephen Bett is doing with language in his latest opus. I call it word jazz: poetry generated as much by sound association as image association; what Charles Olson called Projective Verse—proprioceptive poetry that lives in the moment and leaps playfully through word association nets not so much to create a thing, as to arrest the movement of the mind as it moves through microcosms and macrocosms of the cityscape, reflecting on and refracting what the poet finds.

Let me lay my cards out. I’ve been in a long love affair with English language haikai poetry (haiku, senryu, tanka, kyoka, zappai, renku); Kerouacian “pops” and Ginsberg’s “American Sentences”; trad to avant garde ‘ku; imagism; found poetry; realist and neo-surrealist styles. So, after a bout of jazz poetry and performance in homage to Miles Davis, and performing cryptocritter/alien poems at kidlit conferences and local bandshell/gazebos (Frank Zappa for Tweens) with my jazz/rock troupe Sasquatch, I’ve been getting low and digging wit, irony, humour, epiphanies, bumper snicker spam-ku, scifaiku, for a good ten years or more.

Hence, I love the paradox of the so-called “wordless poem,” erasure, minimalism in all its modes, modern and post-modern.

Bett’s his own man here. He’s absorbed the lessons of Donald Allen’s New American poets—the Objectivists, Beats, Black Mountain, New York and San Francisco schools, etc.; the Canadian Tish poets’ experiments with vernacular phonological phrasing in open form; the studious avoidance of the “burnished urn” Modernist reliance on myth, metaphor, and intellectual conceits, dense allusion, tight boxed containers.

Not that Bett’s poems aren’t marvelously allusive; the bric-à-brac of pop culture is all here: movies, cell phones, the Web, selfies, Tweets and all manner of squawks from the Interface. But there is nothing overtly confessional and the stitches and strophes are as comfortable and companionable as a Tetley Tea bag or new silk pyramid of the latest craft tea. The allusions are to pop culture events: post-modern texts, not obscure texts. The reader is invited in—to squalid cold-water flats of yesteryear newly converted for the addicted and down-and-out of the lower east side of Vancouver, with sparking bare wires spitting between poles, maybe—but, no matter: the urban experience touches everyone and the reader will supply his or her own meta-narratives where the minimalist directive of the poet’s overarching narrative allows.

This is minimalism for readers who like their poems fat: rich, but sans impasto or ornament. A book of raw wire in the city: edgy, tense, sharp, angular, dangerous— in the electrified, computerized grids of cityscape we inhabit, and in the boxes we place each other in and peer out from; pole to pole down the dirty low-rent boulevard, in back alleys, out to suburbia, as we attempt to touch through wires and wireless interfaces, en face, live and in person in an age of celebrity cast-off culture and relationships.

At the heart of the book and appearing late in the accumulating narrative—the overall alienation we 21st-century zombie citizens feel facing globalization and its feral children—is the story of a dissolving relationship, the man too earnest and accepting; the woman raging and fading into madness. But nothing is cloying or mawkish or sentimental, or even confessional; instead we shift easily from a sort of Special Victims Unit episode of macro family skeleton news:

Then there was cousin

Billy (Edinburg)

down the shop for smokesWife and baby daughter

at home for five

minutesTwenty years later

detective tracked h

im to NYC(Those Godawful Streets of Man (64’” St.)

to deeply personal, eviscerating sorrow:

When anger turns

to rage he could

still hit “on”

you rather than

“at” you,

How you got

so goddamn

deep under

his, skin, you

are the leeches

you are the

Borderliner

the zombie

the drain

down which

he disappears— . . . (69’11 St.)

with grace and elan.

Musically, rhythmically, the poet is adroit, fluid, as graceful as Sonny Rollins on a good day:

Distress message received,

absorbed, there is no point

but feeling puts thereWhat felt like such joy

rides out despair

runs down, so

godawfullike the speed up high

when it comes

crashing down—Those Godawful Streets of Man (I O’” St.)

You can feel those tight turns, drops, and ascents as you might on a carnival ride; Bett doesn’t waste a word, but pastes you to the back of your vernacular cage. You are in for the ride.

Each piece in the series is entitled with the overarching title and a street number: Those Godawful Streets of Man (151 St.), ... (2”d St.), etc., and each can be read as a separate lyric poem or as a shifting architectonic set of narrative/lyric plates, a long poem sequence.

Line for line, strophe for strophe, image for image, Stephen Bett’s latest delivers the news, along with the tart taste of jazz and blues.

Richard Stevenson has just retired from a thirty-year gig teaching for Lethbridge College. His latest publications (all forthcoming) are Fruit Wedge Moon: Haiku, Senryu, Tanka, Kyoka, and Zappai, (with b&w photography by Ellen McArthur); Rock, Scissors, Paper: The Clifford Olson Murders, and The Heiligen Effect: Selected Haikai Poems & Sequences.

This review first appeared in Pacific Rim Review of Books #20